How We Learn

The neuroscience of learning

My first couple of weeks in college have been mesmerising. With a collection of more than 12 million print volumes across 6 libraries — including the Mansueto Library that looks like a spaceship — it’s easy to see why The University of Chicago is regarded as an intellectual powerhouse.

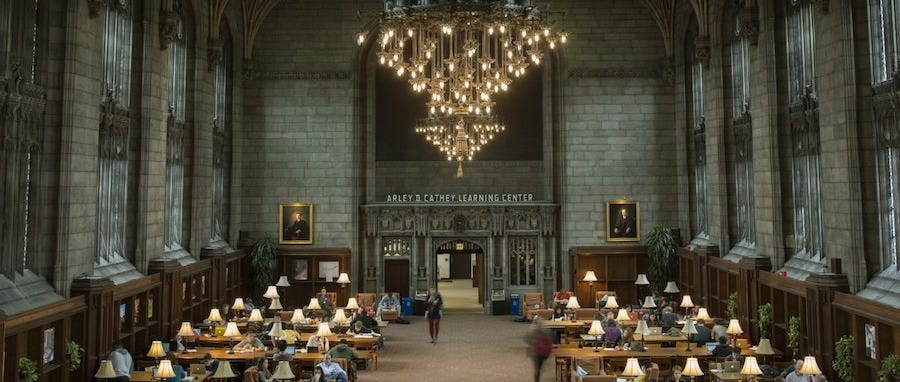

But one of the more interesting spots on campus — one that feels like it’s pulled right out of Hogwarts — is the Arley D. Cathey Learning Center. Quite an interesting name linguistically, isn’t it? Not library, not reading room, but learning center.

That got me thinking: how do we learn? How does the experience of learning relate to the physical processes of neurons in the brain? Are all methods for studying and note-taking equally effective, or some more so than others? Let’s find out!

Active v/s Passive

Right now, I’m taking a class called Honors Calculus (Inquiry-Based Learning). Here’s how it works. There are no lectures and no textbooks. Students prove theorems on their own and volunteer to present these in class. The professor then guides the interaction that follows, often discussing different ways of proving the same theorem. Fun!

At the most basic level, there are 2 ways of learning: active and passive. Active learning, like my math class, involves deliberate practice by solving problems. Passive learning, like most high school and college lectures, involves listening to someone else solving problems. In some sense, active learning is bottom-up, while passive learning is top-down.

What research shows is that in terms of understanding — being able to reproduce ideas with explanations, at will and from scratch — active beats passive every single time. It’s not even close. The paradox is that active learning is effortful and uncomfortable at first, while passive learning feels easy.

A gym analogy is useful. To strengthen your muscles, you need to lift weights. This is difficult, but it will yield results. Watching others lift weights is of no value.

But what I find even more interesting about experimental findings is that active learners show epistemic humility. Have you ever played the card game where you predict the number of tricks you’ll make? This is similar. Not only do active learners know more than passive learners, they are also epistemically humble — they think they know less than they actually know.

Optimal Study Methods

The simplest way to implement this is in how we take notes. Most people take notes by simply transcribing what the book or speaker is saying. The much better way is to take notes by asking questions.

For example, instead of writing ‘Thiel says philanthropy is a form of penance’, one could write ‘What does Thiel think about the European v/s American views on philanthropy?’

This way, reading notes becomes an active process of thinking about big questions and re-deriving ideas, instead of passive review.

Here are some other ways to optimise learning:

Study alone, not in groups.

Eliminate distractions, set your phone to ‘do not disturb’, turn notifications off.

Don’t slog in one long session. Instead work for 45-60 minutes on, 15 minutes off.

Get deep rest, either in sleep or through yoga nidra. The re-wiring of neurons is catalysed by deep work. Neural connections physically change during deep rest.

Teach fellow students who are in the same class (or anyone else). Teaching out loud in complete sentences forces you to understand an idea deeply.

In some sense, all of the world’s knowledge is available at our fingertips, in the form of e-books, YouTube videos and more. For example, MIT freely shares lecture recordings, slides and homework problems for every single class — in theory, anyone can get an MIT education.

But learning is not a resource-availability problem: it is a motivation problem. Climbing the stairs to the top floor of the library is physical effort — yet, I speculate that doing so will (subconsciously) lead to more productive learning.

Feedback and reading recommendations are invited at malhar.manek@gmail.com