Shannon, PayPal and Chess with Jimmy Soni

A chat with the author of The Founders, A Mind At Play, Rome's Last Citizen and Jane's Carousel

I recently had the good fortune of speaking with one of my favourite authors, Jimmy Soni. His books on Claude Shannon (A Mind At Play, my notes here) and the PayPal story (The Founders) are among the best I’ve read — and he approaches his writing with meticulous research and the mindset of ‘volume builds quality’.

Behind The Scenes

When I read Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman’s biography of Claude Shannon, A Mind At Play (my notes here), I was reminded of something I’d read in James Carse’s book Finite and Infinite Games.

Here’s what I wrote in an email to the authors, quoting from Carse’s book: “…‘To be serious is to press for a specified conclusion. To be playful is to allow for possibility’. Given the formulation of information as the resolution of uncertainty (H = - p log p - q log q), it seems like being playful is being information-rich.”

Rob Goodman very kindly wrote back: “That's a really insightful connection between the ideas of playfulness and information theory. It makes sense to me, and I wish we had thought to make that connection in the book!”I enjoyed A Mind At Play so much that I gifted a copy to the Managing Director of Morgan Stanley India.

Fun fact: Jimmy Soni spent more years researching and writing the PayPal book than the time in which the PayPal story itself played out (from creation to the eBay sale)! It’s a testament to his meticulous research, which shines out when one reads his books.

MM: Let me start by asking you about chess: Claude Shannon played against Mikhail Botvinnik; Peter Thiel played 10 simultaneous chess games at the PayPal IPO (and is said to have been impressed by DeepMind founder Demis Hassabis’ chess skills); and your book The Founders segments the PayPal story as Sicilian Defense, Bad Bishop and Doubled Rooks. Can you talk me through the chess connection? [For interested readers, Raymond Smullyan’s book The Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes is brilliant.]

JS: That's great. It's an observation that actually nobody has made before about the connection between the two books. You know, it's interesting, I hadn't even really thought about it until now. I don't think it's an accident that chess features in both books — one about Claude Shannon, who's an electrical engineer, a math professor and founder of information theory; he was an avid chess player, and was pretty talented. He wasn't competitive in the way that others were like at Bell Labs, but he definitely could hold his own. He wasn’t trying to be a chess virtuoso, but Shannon did build one of the world's first chess playing machines; I think it was actually the world's first chess playing computer. It's called Endgame. It was designed to play the last several moves in a game. He actually wrote an academic paper about chess; he also did some really breakthrough work in calculating the maximum possible combinations of moves in chess, things like that. So there's a real passion there.

And then on the PayPal side, it's a much bigger part of the story. Peter Thiel was exceptionally good at chess — at one point he was the top player under 13 in California, I think, something like that. I don't know the facts quite right there. But he was very talented.

And I will tell a couple stories. One is that actually one of the earliest investors in Confinity [which later merged with X.com to become PayPal], found Peter because of chess. Even while Peter was involved in the creation of Confinity, he was playing competitive chess on the weekends and going to tournaments. And there was a gentleman [Edward Bogas] who he had met through playing chess. When Confinity was looking to raise its friends and family round, he contacted this guy.

He's not someone that anybody would know, he's not anybody famous. He's not a venture capitalist. So I Googled his name and I found a phone number on one of those sites that lists four or five phone numbers, and hopefully one of them works. So I call this one number, that's a 650 area code. I call it and I said, “Hi, my name is Jimmy Soni, I'm working on this book about PayPal. I think you were an investor in PayPal very early when it was called Confinity. I don't know if you're the same person that's listed on this document. But I would love to talk to you if you are.”

And I'm thinking, this is gonna go nowhere, right? And I get a call back right away and this person said, I am the same person and I did invest. And I'll tell you a story. The story goes like this.

So, he had played Peter a few times. And Peter shows up at this guy's house and he says, “I'm building this company and I'd love to have you invest.” And the guy goes to the back, writes a check for a decent amount of money and hands it to Peter right away.

And I asked this guy, I said, “Wait a minute, this doesn't make any sense. You don't really know Peter — you know him as a chess player. How did you know that this was going to work out?” [Because the investment worked out very well for him.] And he said, “When I sat across from Peter on the chessboard, his chess style was merciless. And I knew that anything that Peter was going to do, he was going to be out to win.”

And so it's interesting because that quality does emerge throughout the story. The folks who were at PayPal weren't just competitive, they had a will to win. I think there's a difference between wanting to do something and wanting to win. It is the difference between players like Kobe Bryant and Michael Jordan and other players who play basketball, there is a desire to win that supersedes their competition. So chess is the place where that came out.

Now, the other interesting thing about PayPal is that it had a lot of talented chess players. Max Levchin (co-founder) and David Sacks (early employee) were both very talented chess players. So you had actually a number of people who were very good at chess. And in the book, one of the things I explore is this culture of game playing: chess, strategy games, poker.

The book has three parts, and I named each part after a different sequence in chess. So one is called Sicilian Defense. And there are two others [Bad Bishop and Doubled Rooks]. At the time, I thought it would be very clever if the sequence in chess was something of a metaphor to the the situation that they were in. And so one of them is called Doubled Rooks, and I think there's something around two power players in that section of the book.

Sicilian Defense, if I remember correctly, is something black can do to respond to a move that white makes, that will give it the advantage. But it's always the case that black is the underdog. And throughout much of its early history, the early iterations of PayPal, they felt like underdogs; they felt like they were never going to win, they felt like they were going up against much better opponents. And so I just had these ideas. And I felt like it was a little bit more clever than calling those sections part one, part two, part three. And I put in the chessboard diagrams because I thought they were visually appealing.

All of this is also tied into the fact that when I was a kid, I played chess. I was not competitive, I was nowhere near as good as the people who were a part of PayPal. But I loved chess growing up, I played with my dad. I have an eight-year-old daughter now, I've taught her how to play chess, we play chess regularly. And so chess is a part of my life. It was a part of the lives of the people that I studied.

And there's this joke that all biography is actually just autobiography. And so now that I'm thinking about it out loud, I'm like, of course, I ended up writing about this. I wasn't writing about baseball players, because I didn't play baseball growing up, I played chess. So it's sort of both very funny and then it's also very much a part of the substance of these cultures, and I don't think that's accidental.

One thing I'll add to this is that, in addition to chess, I’ve learnt that there's a high degree of overlap in video game culture and tech culture. And maybe that seems obvious to people. But I would go one step further. I heard this story, I think it was on the Tim Ferriss podcast about how Travis Kalanick, one of the co-founders of Uber, is actually one of the world's greatest Wii Tennis players or was at one point (“Travis Kalanick was ranked No. 2 in the world at Wii Tennis” — source).

One of the things that I found was that Elon Musk was an avid StarCraft player. And I would say that there's a difference between people who are casual gamers and people were very competitive video game players. And my understanding through both my own research and through other interviews and other things, is that Elon is a very competitive video game player.

And there was actually a culture at PayPal also of video games being played at the end of a work day. One of the things that happens in these cultures is there's a thin line between work and fun. So if you're at the office on a Saturday, you might be working, but you might also be playing video games for six or seven hours. And I think that's unique to this kind of culture.

Now granted, this is all again, with the caveat of, I played video games growing up — I grew up playing StarCraft, I grew up playing Doom and Duke Nukem and all these video games. So maybe I was just looking to write stories about this stuff.

MM: You gave a Ted Talk at Duke, where you spoke about learning history in terms of people and stories rather than facts to memorise — and your books exemplify this. Can you talk me through your own stories and writing processes?

JS: There's this curious thing in the lives of writers — people think writers’ lives are more glamorous than they actually are. And particularly if you write books — this is less true of just general writing on the internet or blogging — people have a tendency to think that if you write books, your life is very glamorous.

And maybe there was an era in which that was true, right? Maybe people think all writers’ lives are like F Scott Fitzgerald or Ernest Hemingway. Actually, a lot of writing is not glamorous at all. It is sitting in a room alone for many hours, just trying to take an idea or a thing that you're thinking about and bring it to life on the page.

Think about the scene: I'm in my apartment, working alone with big stacks of paper, it's not that interesting. It's not like I'm fighting in a war or leading a revolution or discovering some breakthrough in science. I am sitting by myself typing, trying to finesse words on a page.

And there's this line and I don't remember who said it, but someone once said that, the more interesting the life, the worse the writing. (For pure writer types.) And I think there's actually a lot of truth to that. Because what happens is good writing comes out of — at least for me, and for many of the writers I admire — it comes out of just daily improvement.

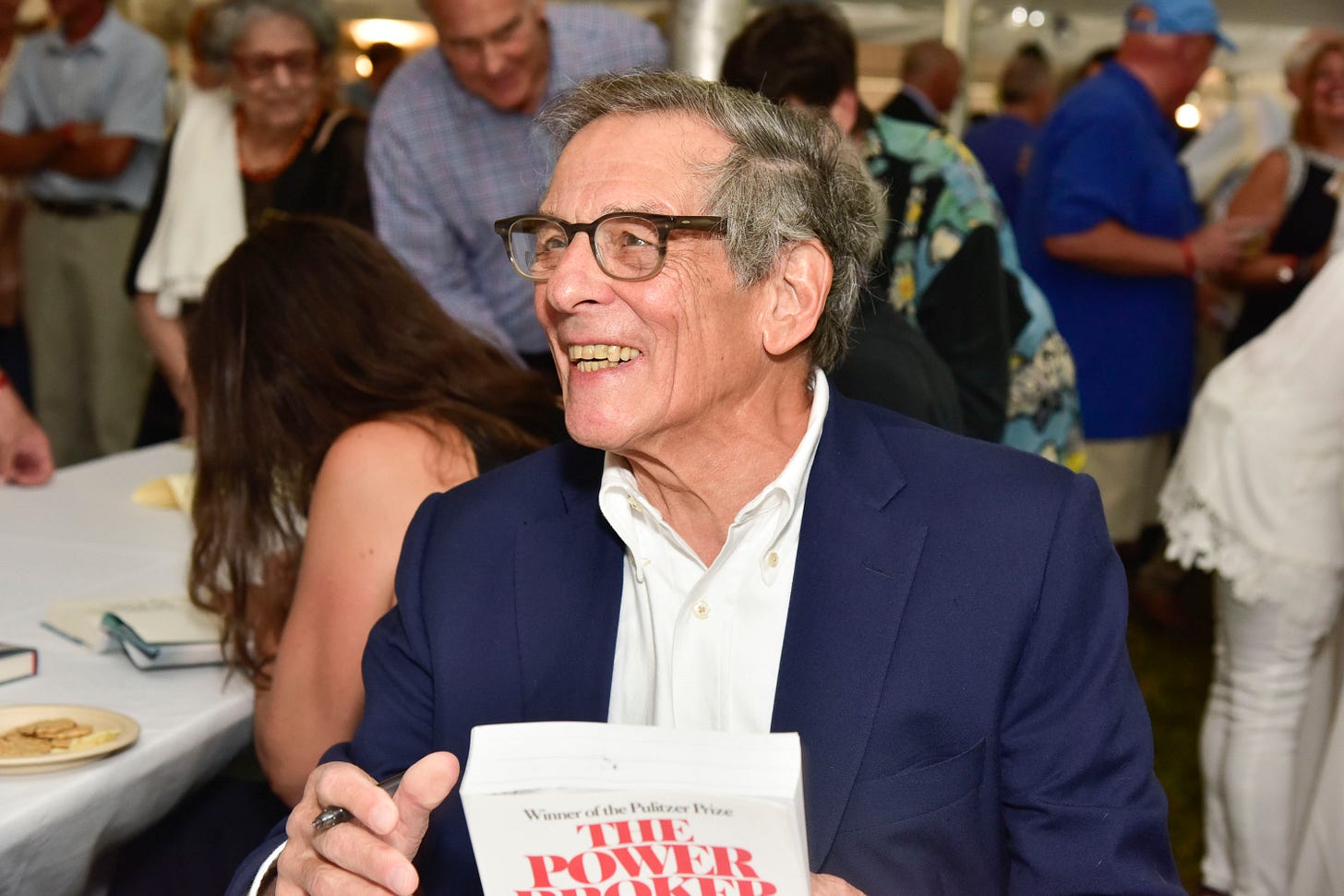

I noticed that in your background, you have Robert Caro’s book — and The Power Broker is a masterwork. But if you were to look at the scenes throughout his life, apart from the interviewing, most of Robert Caro’s life was just getting up every day, putting a suit on, going to work in his typewriter, and doing the same thing over and over and over again.

I think that my life has been interesting: I've had the opportunity to sit with some of the most prominent people in the world and get the chance to tell their stories. But I don't want people to think that the writing life itself is glamorous. And I would say that if you're looking for glamour, like, there's way better places to find it.

People think that what I do is go to cocktail parties — and it's actually very much the opposite. I generally don't socialize — especially when I'm in a true book-writing mode. I don't want to be distracted, I say no to a lot of invitations.

This is true of a lot of authors who are working on long form projects; the project just becomes a part of you, and it takes over every other part of your life. It's hard to do anything else. I suppose there's something interesting about the process of flying all over and meeting these people, but the truth is that a lot of writing is just boring, basic, “get up and do the work” kind of stuff.

MM: In your interviews with these subjects, of course you have done Caro-esque research but how do you go about formulating questions? Do you think about specific word choices and the phrasing and framing of the questions you ask? Are there examples of actual questions you asked that you could share?

JS: Yeah, these are great questions. The answer is yes. I think about all of that stuff a lot. One of the biggest things for me is that — and what works and why I think my books might be a little different than what's out there — is that I try to ask interesting questions. And I spend a lot of time on the front end, figuring out what a given subject has already said about a topic. And then I eliminate most of those questions from the list that I want to ask.

And so that seems very obvious. But here's why it's important. If you're someone important, or interesting, or famous or wealthy, you're often in the position of being asked the same questions over and over again. So if you're David Sacks, or Peter Thiel, or Elon Musk — you just get asked the same boring questions over and over again. So if I, as an interviewer, come in, and I ask the same boring questions, then they will be bored. Or they'll just give me the answers they're accustomed to giving — they become rehearsed.

If you're writing a book, that's the opposite of what you want as an author, because you actually want new material. I want Elon Musk to be answering questions that he has never answered before. I want to ask him something where he says to himself, “oh, never thought about that.”

I'll give you an example. One of the questions I asked Elon — this is at the beginning of one of our interviews — I said to him,

“I'm gonna go in a little bit of a different direction here. We've talked a lot about PayPal. One of the areas I'm writing about is the death of your best friend who died at the age of 54 or 55 (correction: 51) — around the age that you are now — and his name is Greg Kouri. My impression from what I've read and learned is that Greg was a really important figure in your life, in the transition from your life as a student to your life as a technologist. And I was wondering if you could say something about him and about the impact he had on your life.”

— A question that Jimmy Soni asked Elon Musk

And I don't think Elon had heard the name Greg Kouri in many years at that point, or at least a little while, because he's not a well known figure. And there was a notable pause. And Elon gave me this line that's in the PayPal book, he said, “Greg was a trickster with a heart of gold.” And then he went on to explain what he meant by that. And it was just one of the best moments in the book, because I had not seen that kind of description, or that kind of reflection anywhere else.

So I knew okay, this is new. I'm trying to add something that isn't there, but the only way to do that is for me to obsessively read everything I could about Greg Kouri. I found Greg Kouri’s widow, I interviewed her for two hours, I did all of this background research before I ever asked Elon that question, because I knew that this is going to be an area where he hasn't spoken about this.

If you were to go to Elon and say, “What's it like to build a startup?” He’d say, go watch my other 25 interviews on YouTube where I've answered that question a million times. But that's the trick. The trick is, ask the question where the subject says, “Hmm, that's interesting.” That's one trick.

The second trick I have found is, one of my principles is you want to look where other people aren't looking. And so if you are interviewing somebody — let's say they're a successful technology investor — if you ask them about technology, or about investment, you're actually likely to not get that interesting stuff. But if you ask them about college, and about their education, you might get more interesting stuff.

And so from my perspective, yes, it was useful to ask Max Levchin about the process of PayPal and how he made it more secure and how he built a technology team; we got to all that later in my interviews. But where I started was with his story of immigrating to the United States. And he's done some interviews on that, so there was a little bit of overlap, it wasn't completely new information. But I went deeper and I was able to ask him about his grandmother, his parents, physics and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

I try to find a way to tap into the thing that someone wants to reflect on, but they have never really been asked about it, or they don't get asked about it that often. It's a hard thing to pull off. And there isn’t an exact science to it. But I find that if you can do that, what you do then is also you build a rapport with a person.

One of the things I tried to do with all my books is I try to bring my characters to life. I don't want them to just be two-dimensional people giving the same answers. I want them to be figures. I can say that you're 5 feet 7 inches tall and 150 pounds — or I can tell a story about your family. The second is a better way of writing. And so for me, the way to do that is to look where other people are not looking.

But the other last thing I'll say — and I could go on this topic forever, interviewing is one of my favorite things to do and also one of the hardest things to do — one of the other things I do in an interview is I try to make it fun. I try to make it enjoyable. I'm not there interrogating you as though you were in a courtroom.

I try to make sure that I really listen to what people say. The most important people in my stories will just cancel the meeting if I'm boring to them, or if I'm uninteresting, or the interviews are not fun. And so you're trying to balance this. It can't just be all humour and good times, it has to be substantive, there have to be some questions that are hard. At the same time, if you are an interviewer with whom they don't actually have fun, then for the kinds of projects that I do, that's a death sentence: you're never gonna get called back, you're never going to be able to get them to respond to you again.

I always tried to make sure that I was asking about things that would be enjoyable to reflect on, in addition to asking about things that would be uncomfortable, or where I really needed substance. I heard from my subjects after the book came out, they said, “one of the reasons that we really liked talking to you or one of the reasons we kept talking to you is because it was actually fun.”

And I would say that I tried hard to make it fun. And that's not at the expense of being hard hitting; it's not at the expense of being serious. It's just that there's so many interviewers I've met, where they go so deep into the facts, they forget that they're talking to a person and not an AI Chatbot.

MM: You’ve spoken about volume builds quality — maybe there are parallels to this in how PayPal tracked their number of users in the ‘World Domination Index’? Could you elaborate on how that loop from volume to quality occurs?

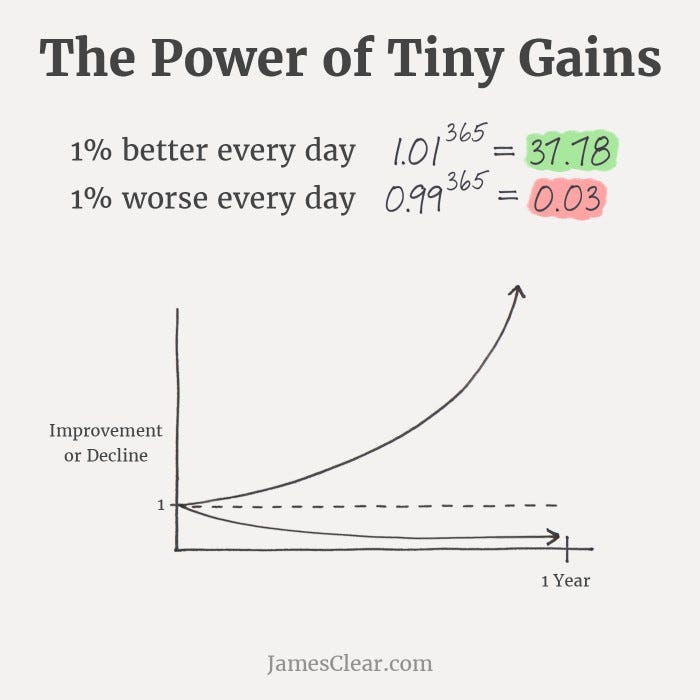

JS: Yeah, it's a good question. This is especially true for writers. where the more you write, the better you get, the more you read, the more adept you are at reading. In those two disciplines, reading and writing, it is like, the more you do it, the more capable you will be. I've yet to meet the person who who violates that equation, or who can short circuit it.

I think that there are many domains where we have been fed the fiction that you can short circuit the outcome without putting in the reps; that you want to get somewhere and you can skip the 10 years, you can skip the 5 years.

But most of the things and people we admire are a by-product of compounding. It's rare that there are overnight successes. You look at any person that's in the headline today. And if you hear something about them you admire, it's highly likely that they did not just get lucky — they did something over a long period of time.

In the domain of music, if you look at somebody like Taylor Swift, it is easy to talk about how she is a billionaire today and how the eras tour is, I think, the highest grossing world tour of all time. People forget that she started doing music when she was like 14 years old or 13 years old. Her process, her desire started at a very young age. If you look at the most successful people in sports, the most successful coaches, the most successful technologists, they all started early and put in a lot of struggles and failures.

Max Levchin had three failed companies and one very modest exit before he started his fifth company, PayPal. Elon Musk started a college business, then had another business (Zip2) and then started PayPal.

Volume teaches you all of these lessons. It's not popular to say because everybody wants a quick way to get the thing they want. I get it. If you see somebody on Wall Street Bets making a million dollars overnight, or you see somebody making $10 million in crypto in a month, you think to yourself, “how do I do that?” I get it. But there are some games where patience, compounding and volume are the only things that matter.

And I would say that is true with writing in particular. The more words you write, the better you get. My third book is better than my first, my fifth book will be better than my third, and so on and so forth. I'm just becoming more talented and knowing what resonates with readers.

In terms of feedback loops, I build feedback loops in by either hiring editors, so I'll just pay people to read my work and then give me feedback. Or you have editors that you work with the publishing houses. And then the internet is the ultimate feedback loop. Especially with quick writing, you put something out, and you can get feedback right away. That's important.

But I think people tend to think that the feedback is more important than the volume. Because the volume is the not fun part. The not-fun part is when, for example, during the middle of The Founders project, I set myself a deadline. My goal was, I need to do 1000 words every day. And I did that for 100 days. I just had to do it. And I did it.

And the volume built a project. But I also thought that by the hundredth day, it was easier to get 1000 words out than it was on the first day. And it was horrible at times; there are times when I would wake up and it's the last thing I wanted to do. I mean, it was just truly horrible.

But I think that success leaves clues. And one of the clues of successful people is whatever they're successful at, they generally just do a lot of it. And the more you do of it, the better you get. It's not a sure thing; accidents and chance can happen, both good chances and bad chances — you can have two people who are identical, and one gets the lucky break and the other doesn't. There are all these other variables, but the truth is, part of the success of most things is volume — just doing more than other people do.

What makes Mr. Beast’s YouTube videos so successful? Well, he started when he was 16 years old, he was doing it for five or six hours a day, for 30 years. You do that and you'll be similarly successful. But I think it's hard for the human brain to operate on such a long time horizon. And so that's why people end up just shrinking the volume, and they go for the quick win.

Feedback and reading recommendations are invited at malhar.manek@gmail.com