Priming and the Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind

"This is superb" - Rory Sutherland

If, like me, you’ve read Daniel Kahneman’s brilliant book Thinking, Fast and Slow, you probably know about the priming effect.

It works something like this: upon reading the words ‘banana’ and ‘vomit’,

your mind automatically assumed a temporal sequence and a causal connection between the words bananas and vomit, forming a sketchy scenario in which bananas caused the sickness. As a result, you are experiencing a temporary aversion to bananas (don’t worry, it will pass). The state of your memory has changed in other ways: you are now unusually ready to recognize and respond to objects and concepts associated with “vomit,” such as sick, stink, or nausea, and words associated with “bananas,” such as yellow and fruit, and perhaps apple and berries.

Similarly, say you read the words ‘wash’ or ‘eat’. You’re then asked to fill the blank: SO_P. The priming effect (also called associative activation) suggests that you’re more likely to complete the word as ‘soap’ in the first case, and ‘soup’ in the second.

What’s more, priming has the power to link ideas and actions, through the ideomotor effect. Reading words like ‘old’ might make you slower to get up or walk, and, conversely, sprinting at top speed may attune you to more quickly recognise words like ‘young’.

When I first read this, I was blown by how subtle changes in our environment can so significantly affect our decisions. A series of questions rushed through my mind. How does the higher-level, emergent explanation of priming get mechanically implemented? What is the corresponding lower-level, fundamental effect in neuroscience? What is the isomorphism between these?

That was perhaps 10 months ago. Like many others, these questions were shelved away into my vast compendium of ‘open questions’, or what Richard Feynman called ‘favourite problems’. I recently found the answers, as well as insights from an unlikely source: comics.

The crux of the answer lies in the pattern recognition theory of mind (PRTM), propounded by Ray Kurzweil in his compelling book, How To Create A Mind.

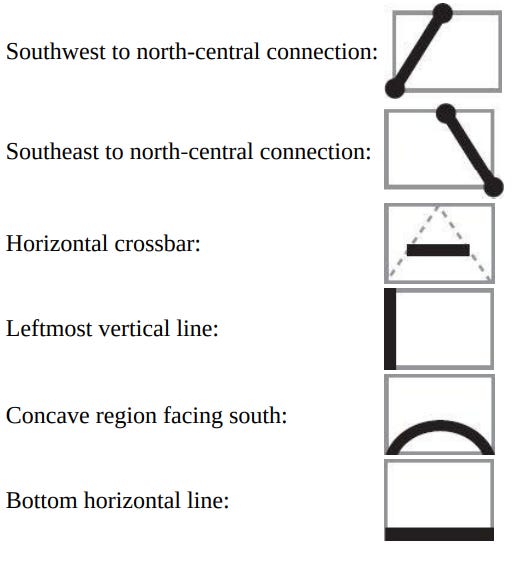

Consider these symbols, each of which is a distinct pattern:

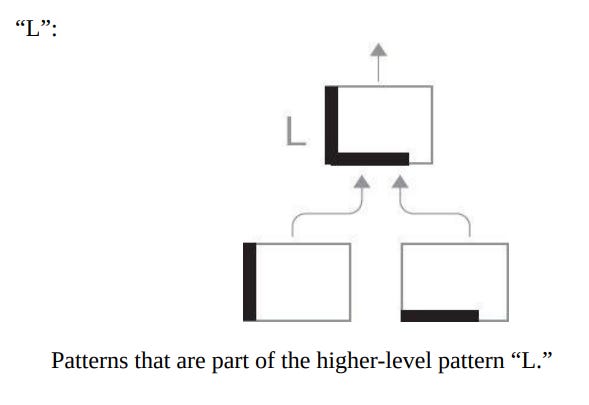

These are inputs to the next higher-level pattern of letters…

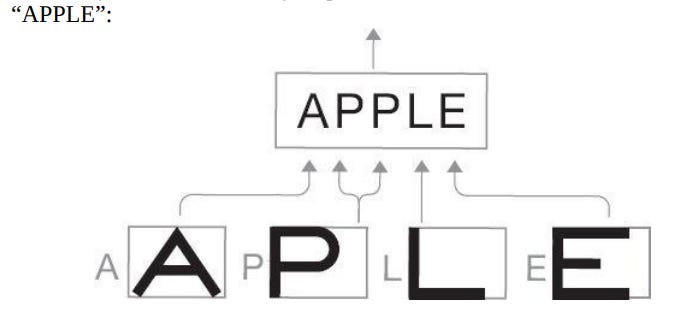

…and these, in turn, are inputs to words:

Stored in the module is a weight for each input dendrite indicating how important that input is to the recognition. The pattern recognizer has a threshold for firing (which indicates that this pattern recognizer has successfully recognized the pattern it is responsible for). Not every input pattern has to be present for a recognizer to fire. The recognizer may still fire if an input with a low weight is missing, but it is less likely to fire if a high importance input is missing. When it fires, a pattern recognizer is basically saying, “The pattern I am responsible for is probably present.”

Now, here is the crucial part. In the above pictures, we saw how lower-level pattern recognisers (for lines) provide inputs upwards to higher-level pattern recognisers (for letters and words). But, saliently, the flow of information is also downwards.

If, for example, we are reading from left to right and have already seen and recognized the letters “A,” “P,” “P,” and “L,” the “APPLE” recognizer will predict that it is likely to see an “E” in the next position. It will send a signal down to the “E” recognizer saying, in effect, “Please be aware that there is a high likelihood that you will see your ‘E’ pattern very soon, so be on the lookout for it.” The “E” recognizer then adjusts its threshold such that it is more likely to recognize an “E.” So if an image appears next that is vaguely like an “E,” but is perhaps smudged such that it would not have been recognized as an “E” under “normal” circumstances, the “E” recognizer may nonetheless indicate that it has indeed seen an “E,” since it was expected.

There it is: priming at a higher level is isomorphic to pattern recognisers and their thresholds at a lower level!

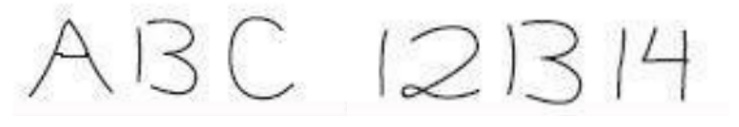

So now you know why, in the picture below, you interpret the left as ‘A B C’ and the right as ‘12 13 14’, when in fact the symbol in the middle is the same in each case.

But this is not the end of our story. Shifting from analytical rigour into the world of arts, a compelling instance of priming & PRTM is waiting to be discovered: comics.

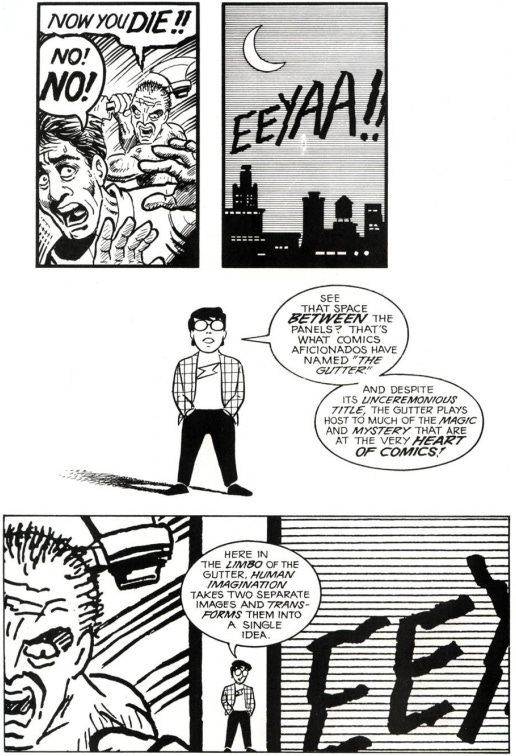

That too in the most unlikely of places: the tiny spatial gap between consecutive comic panels. As Scott McCloud explains in his brilliant book, Understanding Comics, closure is when the mind creates a narrative to reconcile the observation of two static frames.

In forms like video or flipping through a picturebook, emergent continuity from fundamental quantisation arises naturally; in comics, however, this is not the case. The neuroscience of priming plays a key role in the pleasurable experience of reading comics (something that I, as a Tintin fan, can attest to!)

There remain, to my mind, several more questions pertaining to the priming effect.

There seems to be a sort of ripple effect in priming: exposure to the word or image ‘orange’ may strongly tune pattern recognisers for ‘juice’ and perhaps weakly for ‘apple’. How might such weak and strong links be rigorously analysed?

Such a ripple effect also probably exists in the temporal dimension. How long does a primed state last? What is the nature of this progression over time? I conjecture this is probably an exponential decrease with time. Is this trend similar to the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve in memory?

Pointers to material on such ideas would be greatly appreciated.

Feedback and reading recommendations are invited at malhar.manek@gmail.com