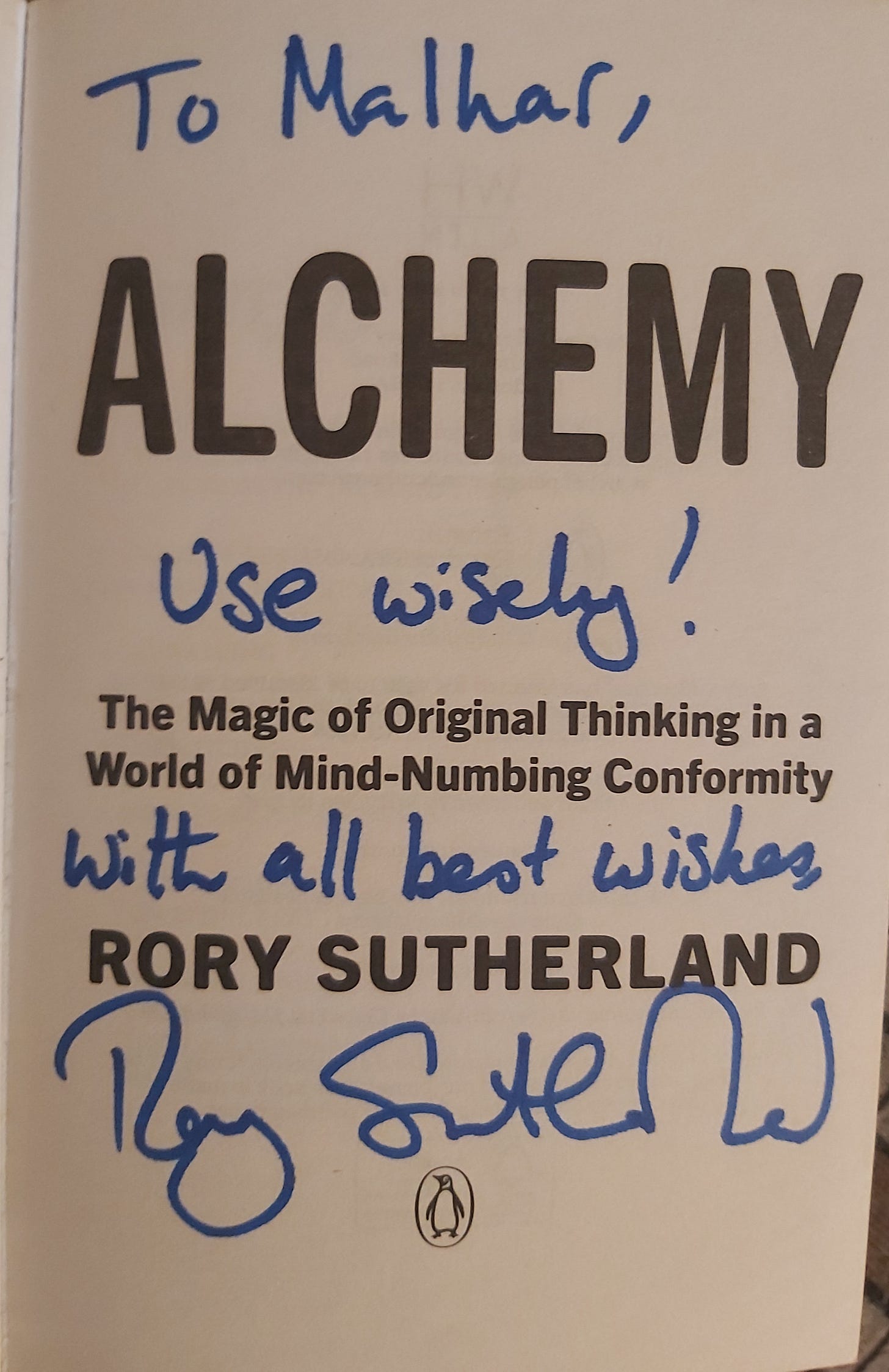

I recently had the opportunity to speak with one of my favourite thinkers and writers, Rory Sutherland. He is the vice-chairman of Ogilvy and an absolute creative genius, as you will find out for yourself if you read his brilliant book Alchemy (which I can’t recommend highly enough) or watch his Ted Talks.

Behind The Scenes

We have a common passion for postal mail — he appreciates the costly signalling involved (both money and time) in sending a letter; I, on the other hand, have been a stamp-collecter (philatelist) and post-office-buff all my life!

We both enjoyed Scott McCloud’s amazing book, Understanding Comics. In Rory’s words, “I picked it up thinking it was kind of silly, but by the end - and I read it on one sitting - I thought it was one of the best books ever written - or indeed drawn!”

I first read Alchemy 2 or 3 years back, and it changed the way I think about perception v/s reality. If a courier service’s 3-day delivery rate is 95%, but customer surveys show that it is perceived to be 70%, greater value can be created by improving perception (taking 70 to 95) than by enhancing reality (taking 95 to 100). In this case, the bottleneck/constraint is not reality but perception. (Theory of Constraints is among the most elegant and important ideas ever, in my opinion.) The parallels with George Soros’ theory of reflexivity are intriguing: improve perception to boost valuations, use high prices to raise equity capital at low dilution, then use this capital to improve reality. Another gem of an insight: cyclists tend to be rude since they pay the price for losing momentum. I can go on and on endlessly, raving about Rory’s genius ideas on placebos, self-fulfilling prophecies and beyond (he is incredibly well-read, as you will find out), but I’d recommend his book Alchemy for more.

He called Mumbai “a fantastic city, amazing city to be in” — music to my ears!

And now, dear friends, here’s Rory Sutherland.

RS: One of the really clever ideas that Eric [Yuan] who founded Zoom had, was he realised that most people attempting to develop video conferencing were focused on the video quality, but actually it’s the sound quality that matters. The human brain can cope with a large amount of pixelation and it can cope with people freezing, but it can’t cope with the voice breaking up. And there are really interesting reasons for this.

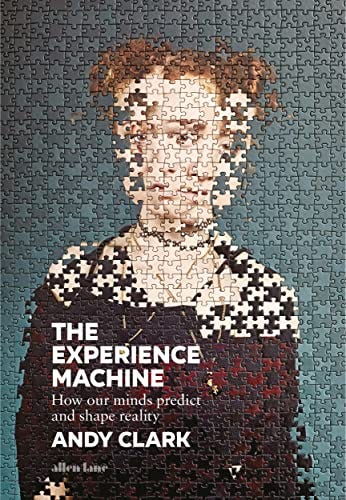

By the way, there’s a book I really recommend you read if you’re interested in this field, which is a book by a British guy called Andy Clark, called The Experience Machine. He has this theory that most of what we perceive is really a prediction — that the brain generates a prediction of what we expect to see, and then we use our eyes, nose, ears etc. to correct, effectively, for prediction error.

It’s very similar to how a JPEG works — so a JPEG achieves data compression by having an expected value for each pixel and it uses data to describe where the value differs from the expected value. And obviously it uses much less bandwidth and much less data to actually work that way.

So the optic nerve — the 6 megapixel or whatever it is that passes through the optic nerve — can concentrate on updating prediction error and alerting us to the unexpected, rather than being wasted effectively generating things that we were expecting to see anyway. It’s a really, really interesting mechanism. It’s an old theory actually, people like von Helmholtz in the 19th century came up with this theory, and what Andy Clark has done in The Experience Machine is he’s taken it forward. He’s taken it further with the benefits of modern neuroscience as well.

[MM: I had sent these ideas to RS before our call: “I remember you saying that the percentage of electric car owners who switch back to petrol cars, is very low. This metric seems to be key to analysing new, disruptive technologies. In reading Richard Dawkins, I found a compelling parallel. The Levinthal paradox in protein folding says that the number of possible paths of a protein is too vast and that sampling all of them would take longer than the age of the universe! Mr Dawkins resolves this using the following analogy: a monkey pounding away at a typewriter will probably take exceedingly long to print a sensible, meaningful English phrase like ‘The Eleven Rules of Alchemy’. But if a correctly-chosen letter/word is fixed in place (akin to an EV owner not switching back), this time reduces dramatically as the search tree is pruned.”]

RS: But I thought your Darwin point is very interesting, which is that it is impossible for monkeys to generate Shakespeare, except if there’s a mechanism where you stick with something that works, and you experiment with something you’re not sure about.

So, it’s very interesting that if you look at evolution, most animals are basically symmetrical, so it wouldn’t make sense to experiment heavily — although there are weird cases, so the exception to that would be the flounder, which is a flat fish that lives on the bottom of the ocean and so the eye that used to be on the bottom has migrated round to the top. So in that case there's this weird fish that would've started swimming vertically with an eye on each side, and then it effectively evolved its behaviour so that it lay flat on the bottom of the sea where it was very well camouflaged. But that's a really unusual case of an animal actually developing asymmetry.

I imagine Nassim Taleb’s point that we have 2 lungs, 2 kidneys, partly for the purposes of redundancy really. The odds of damaging your eye — I just had a retinal detachment actually, which until 1930 couldn't be treated, so if I'd been a one-eyed person before 1930, I would be completely blind for the rest of my life. But there are two happy things: one is they can now treat it, and the treatment is affordable which I imagine it wasn't in the 1930s; and secondly, because I had a second eye I was able to function fairly well. It strikes me there's a reason we have 2 of things.

The other reason is that symmetry is highly desirable for movement to the point where Robert Trivers actually investigates the correlation between joint symmetry and atheltic performance in Jamaican atheletes. There’s this correlation between how symmetrical your joints are and how fast you can run.

But your point’s very very good, it’s a pity that more people in marketing haven't read enough evolutionary science.

MM: Have you thought about how that relates to redundancy in language?

RS: So there’s a wonderful thing called the check digit, isn’t there? The way a check digit works in a credit card is that if you type 1 wrong number, or if you type 2 numbers the wrong way around, it immediately says there’s a fault here. There's always the potential that you could type 2 wrong digits and still get the check digit working but the most common errors which are transposition of two digits, or one mistyped digit, or one digit typed too often — the check digit is the last digit which is a product of the previous 15, and it effectively says “this one's okay”.

So you need to have a certain amount of redundancy. Obviously, if you had hugely efficient language, then you could have comical misunderstandings all the time. I always think it’s laughably stupid that in American English they produce “can” and “can’t” almost the same way.

In German, although it is “eins, zwei, drei” for “1, 2, 3”, if you’re reading your phone number over the phone, you’d actually say “zwuo”, not “zwei”, for “2”. There are a few other things in German where there is a very useful other word to avoid misunderstandings.

It’s interesting that there has to be redundancy in ordinary, oral communication; its different in instantaneous digital communication where you have a return channel. The other guy was Claude Shannon, wasn’t it, who did a lot of work on this?

MM: Exactly. His information theory equation involved an expression for information in bits as a function of logarithms of probabilities. [Claude Shannon is also one of my idols, along with Richard Feynman. The Shannon biography by Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman, titled A Mind At Play, is brilliant.]

RS: I think one of the best things that has happened in the last 5 years is what we're doing now, which is that Zoom has replaced email, partly because email writing doesn't make sense for one-to-one communication. It makes sense for text messages like "are you there yet?" but for anything longer it doesn't make sense because we can speak much faster than we can type. But of course, if you're writing for an audience of 20,000 people, that obviously has time advantages.

The other thing is we can read a lot faster than we can listen. So there’s a benefit to the recipient in receiving email, but to the sender it’s a big pain.

RS: By the way, before I say anything else, I’ve got to say a big thank you to India. I was talking to my publisher about 2 weeks ago and India is one of the countries where it’s had really great success. It’s very difficult to get bookshop sales in the UK, it’s sold well in the US and continues to sell well on Amazon and in Kindle form, but India is the big bookshop success. I noticed when I was last in India, there was a copy on sale at Hyderabad’s airport bookshop.

There’s a problem in Britain, which is that the main high-street bookshops have very little storage space. And so all they’re really interested in is taking a Dan Brown blockbuster or a J. K. Rowling, filling the bookshop with 27 crates of J. K. Rowling, and they’re not interested in anything that isn’t in the top 3% of popular sales, not necessarily in volume of sales over time — my book sells quite well over time — but B2B books don’t sell instantaneously in the way that novels do. So I’ve got a big thank you to the Indian bookselling market for doing such a great job of selling Alchemy.

RS: But you mentioned asymmetry, and if you look at the way emails breed, so you look at it from the point of view of, dare I say, eugenics. Unimportant emails tend to go to a lot of people, and important emails tend to go to just you. So if people hit “reply to all”, you have this fundamental problem that unimportant events fill your inbox and the important stuff gets buried.

There’s also a really interesting question about email, if you look at it from a systems thinking point of view — I’ve always wondered about this. A really interesting point of view is that actually, the reason we have a calendar and we have email, is they’re considered to be separate things, because they were historically: you had post, and you had a diary, which was a physical device. So computer designers, when they designed the interface, had a calendar and they had a communications vehicle. Actually, email and diary should be the same thing, by which I mean, it should say “go to this meeting OR read this email”. So really you should have a calendar which says these are the things you need to read, people you need to meet and places you need to go — they should be the same software. I’ve had crazy situations where I’m reading emails all about my flight and meanwhile there’s an email saying the meeting’s cancelled.

The other thing is, notifications on the mobile phone have become useless because there’s no costly signal. So my phone goes “ding” whether my daughter’s in a car accident or there’s a special offer of “save 5%”. Now, okay, I could go through the various apps, but if there were a costly signalling mechanism, you could say “this is really important, I’m going to pay 10 pence and have the phone make a huge alarm noise instead of going ‘ding’”. To some extent, the physical post had that — you could tell from the stamp (first class, second class) and handwritten envelope.

When you don’t have a costly signalling mechanism in communication, it basically devolves to meaninglessness. What’s happened is that the burden of prioritisation in communication now falls on the recipient, not on the sender. [MM: Game theory provides another fascinating perspective on this. Consider the TCP backoff game, for example, where the Nash equilibrium results in self-interested agents flooding the channel with information, leading to a locally-optimal but globally-suboptimal outcome.]

The lack of 'skin in the game' for the sender is a problem we need to solve. You could solve it quite easily, though not infallibly, by simply requiring senders to mark their emails with a level of priority. Of course, someone could mark everything high priority, but people who did that regularly would get blocked and unsubscribed. And most people know that would be a bad thing to do and they wouldn't do it because there'd be social sanction.

Currently, email has neither a costly signalling mechanism (pay x price to indicate high priority) nor social sanction.

Shannon was looking at the transmission of information. But there is a secondary dimension of 'to what extent should you trust the information?', which isn't included in the Shannon model — you're assuming the sender is accurate in who they say they are.

Because email was designed by people who were Shannonites aiming for maximum efficiency and accuracy of transmission, they didn't spend enough time thinking about how you reliably signal importance and priority, and in what mood you should reply to something. I get tons of Christmas cards, you probably have Diwali cards, but it would be funny if you designed an envelope to look like a bill but inside was a Christmas card.

RS: By the way I was once studying how Amazon became so successful in India and I got into a rabbit hole about the Indian postal service, its history etc. The key insight Amazon had in India was, “we don't need to set up our own delivery infrastructure, it already exists” — and that worked like magic.

By the way, there were some countries that decolonised who said, “we'll get rid of all that [colonial] stuff, we'll start afresh”. And where India was absolutely brilliant was you said “we'll keep whatever works and we'll get rid of the other stuff”. What fascinates me is you're a democracy of 1.5 billion people that basically works. It's not top-down design, it's all bottom-up. For example, that wonderful system you have in Mumbai where your food is delivered to work at lunchtime: it's all bottom-up. That's why I've been saying for the past 10 to 20 years that the prospects in India for economic growth and innovation are much greater than China. The Chinese form is artificial and top-down, India's form is evolutionary and bottom-up.

I used to get really annoyed by British and American businessmen who went on and on about China. Of course, they liked China because you only had to talk to one person; you found the boss guy, you talked to him and that was it, everything was decided. Of course in India it's brilliantly messy and experimental and bottom-up.

There was this guy called Field Marshal Cariappa, who made the decisive decision that the Indian Army would never get involved with politics. In China, the Red Army is not the army of the country China, but the army of the Communist Party, which is a freakishly weird thing.

RS: In evolutionary science, there are a lot of butterfly effects (chaos theory, butterfly flapping its wings leads to a hurricane in another). I'm very interested in evolution; for example it's a random decision whether an animal evolved a convex eye or a concave eye. Now, it turns out that is really decisive, because you can evolve from a concave eye to a lens, and then the whole thing of the iris, light control, magnification and focus. But a convex eye, which insects have, you can't do it. If you wanted a fly to have the vision quality of a dog, its eye would have to be 3 feet across.

Physics is a science of how things are, a science of things that don't change. And evolutionary biology is a science of how things do change. And I think it's really, really important to have both.

In evolutionary biology circles, you can't mention Steven J. Gould because he started to believe in group selection, as did E. O. Wilson and Darwin, and as do I. But in current evolutionary science, that's a no-no, it's all happening at the level of the individual and the gene. But of course, evolution can happen at the level of a group.

[MM: Here’s an extract on this idea from Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon — “From an evolution standpoint, what was the point of having people around who were not inclined to have offspring? There must be some good, and fairly subtle, reason for it. The only thing he could work out was that it was groups of people—societies—rather than individual creatures, who were now trying to out-reproduce and/or kill each other, and that, in a society, there was plenty of room for someone who didn’t have kids as long as he was up to something useful.”]

I would even go further to say that humans have been partly selected for by dogs. [MM: Kind of like “the wand chooses the wizard” from Harry Potter.] This is a really weird theory, but at the absolute low point of the Ice Age, the 30,000-or-so Homo sapiens who survived were probably those who knew how to domesticate dogs. Now that means that dogs would disproportionately domesticate humans who were kind to them…

[MM: We ended our call with my reading out an extract from Ashlee Vance's biography, Elon Musk: “The engineers were constantly baffled by what Musk would fund and what he wouldn’t. Back at headquarters, someone would ask to buy a $200,000 machine or a pricey part that they deemed essential to Falcon 1’s success, and Musk would deny the request. And yet he was totally comfortable paying a similar amount to put a shiny surface on the factory floor to make it look nice.” If this intrigues you, I can think of no better book to read than Rory Sutherland's Alchemy!]

Feedback and reading recommendations are invited at malhar.manek@gmail.com

Wow Malhar! This is a huge milestone.

I am a fan of Rory. How did you get in touch with him?