Bell Labs, Florence and Scenius

"My first stop on any time-travel expedition would be Bell Labs in December 1947" - Bill Gates

At its height, Bell Laboratories — the New Jersey-based industrial R&D arm of AT&T — was the birthplace for an extraordinary number of technological inventions. Researchers there invented the transistor, photovoltaic (solar) cell, and laser. They built the fax machine, the UNIX operating system, and the C programming language. They discovered cosmic microwave background radiation, pioneered information theory, and won 9 Nobel Prizes and 4 Turing Awards. Jon Gertner’s wonderful book about Bell Labs is aptly titled The Idea Factory.

About an hour away — from the Bell Labs HQ at Murray Hill to Einstein Drive in Princeton — is another intellectual juggernaut: the Institute for Advanced Study. IAS was home to legends like John von Neumann, J. Robert Oppenheimer and John Nash. Albert Einstein and Kurt Gödel famously went on walks together. Even today, leading researchers like Edward Witten and Juan Maldacena are at IAS. In the words of a friend who is a physics PhD candidate, “IAS will set a problem and every other university will work on it”.

Musician Brian Eno calls this phenomenon “scenius”, or scene-genius. Throughout history, there have been numerous instances of scenius:

Plato’s Academy (considered to be the world’s first university; see The School of Athens, featuring Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Euclid, Pythagoras and others)

RAND Corporation (“It attracted some of the best minds in mathematics, physics, political science, and economics. RAND may well have been the model for Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, about a RAND-like organization full of hyper-rational social scientists — psychohistorians — who are supposed to save the galaxy from chaos”; see Sylvia Nasar’s A Beautiful Mind)

Fairchild Semiconductor (the future founders of Intel, Kleiner Perkins and others were part of the “traitorous eight” that founded Fairchild; see Sebastian Mallaby’s The Power Law)

MIT Building 20 (Bose loudspeakers, LIGO gravitational wave antenna project, and Chomsky grammars all originated here; see Cal Newport’s Deep Work)

Los Alamos (the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos created the world’s first atomic bomb; see Richard Feynman’s Surely You’re Joking Mr. Feynman)

The “PayPal Mafia” (the founders and early investors in SpaceX, Tesla, Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn and Palantir were all once at PayPal; see Jimmy Soni’s The Founders — or my interview with the author)

Bureau of Municipal Research, New York (the trio of civil reformers, Allen, Bruère and Cleveland — ABC — who worked from 261 Broadway NYC and pioneered a scientific approach to government; see Robert Caro’s The Power Broker)

Even Warren Buffett recognises the phenomenon of scenius — Charlie Munger, Ajit Jain, Greg Abel and Buffett himself all lived in Omaha at some point. As he asks,

So what is going on? Is it Omaha’s water? Is it Omaha’s air? Is it some strange planetary phenomenon akin to that which has produced Jamaica’s sprinters, Kenya’s marathon runners, or Russia’s chess experts?

— Warren Buffett, in Berkshire Hathaway’s 2023 letter to shareholders

Let’s find out!

Valleius, the Roman philosopher, was the first to offer a theory for why geniuses often appeared, not as lonely giants, but in clusters in particular fields in particular cities. He was thinking of Plato and Aristotle, Pythagoras and Archimedes, and Aeschylus, Euripides, Sophocles, and Aristophanes, but there are many later examples as well, including Newton and Locke, or Freud, Jung, and Adler.

He speculated that creative geniuses inspired envy as well as emulation and attracted younger men who were motivated to complete and recast the original contribution.

— Sylvia Nasar, in A Beautiful Mind

In this spirit, here are some of characteristics that I’ve seen recur in numerous instances of scenius.

Combining Theory and Practice

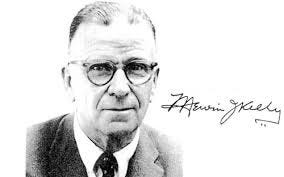

At Bell Labs, the man most responsible for the culture of creativity was Mervin Kelly … His fundamental belief was that an “institute of creative technology” like his own needed a “critical mass” of talented people to foster a busy exchange of ideas.

But innovation required much more than that. Mr. Kelly was convinced that physical proximity was everything; phone calls alone wouldn’t do. Quite intentionally, Bell Labs housed thinkers and doers under one roof. Purposefully mixed together on the transistor project were physicists, metallurgists and electrical engineers; side by side were specialists in theory, experimentation and manufacturing.

Like an able concert hall conductor, he sought a harmony, and sometimes a tension, between scientific disciplines; between researchers and developers; and between soloists and groups.

— An article by Jon Gertner in the New York Times

Similarly, Elon Musk fused the design and engineering aspects of his rockets and cars.

Musk restructured the company so that there was not a separate engineering department. Instead, engineers would team up with product managers. It was a philosophy that he would carry through to Tesla, SpaceX, and then Twitter. Separating the design of a product from its engineering was a recipe for dysfunction. Designers had to feel the immediate pain if something they devised was hard to engineer.

— Walter Isaacson, in Elon Musk

Enabling Serendipity, or Expanding the Luck Surface Area

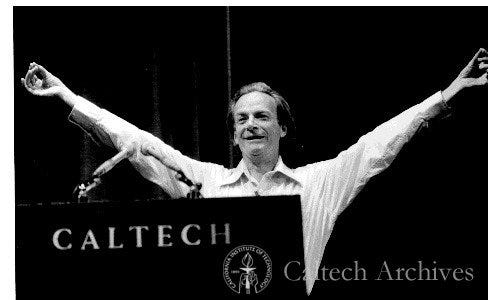

You know how Richard Feynman was once recruited by the University of Chicago, which offered to double his salary or something like that. He was asked, “Why wouldn’t you leave Caltech and take this offer?” and I think—to paraphrase—he said, “At Caltech, if I moved a meter or two, I would be in collision with somebody who will excite my interest.”

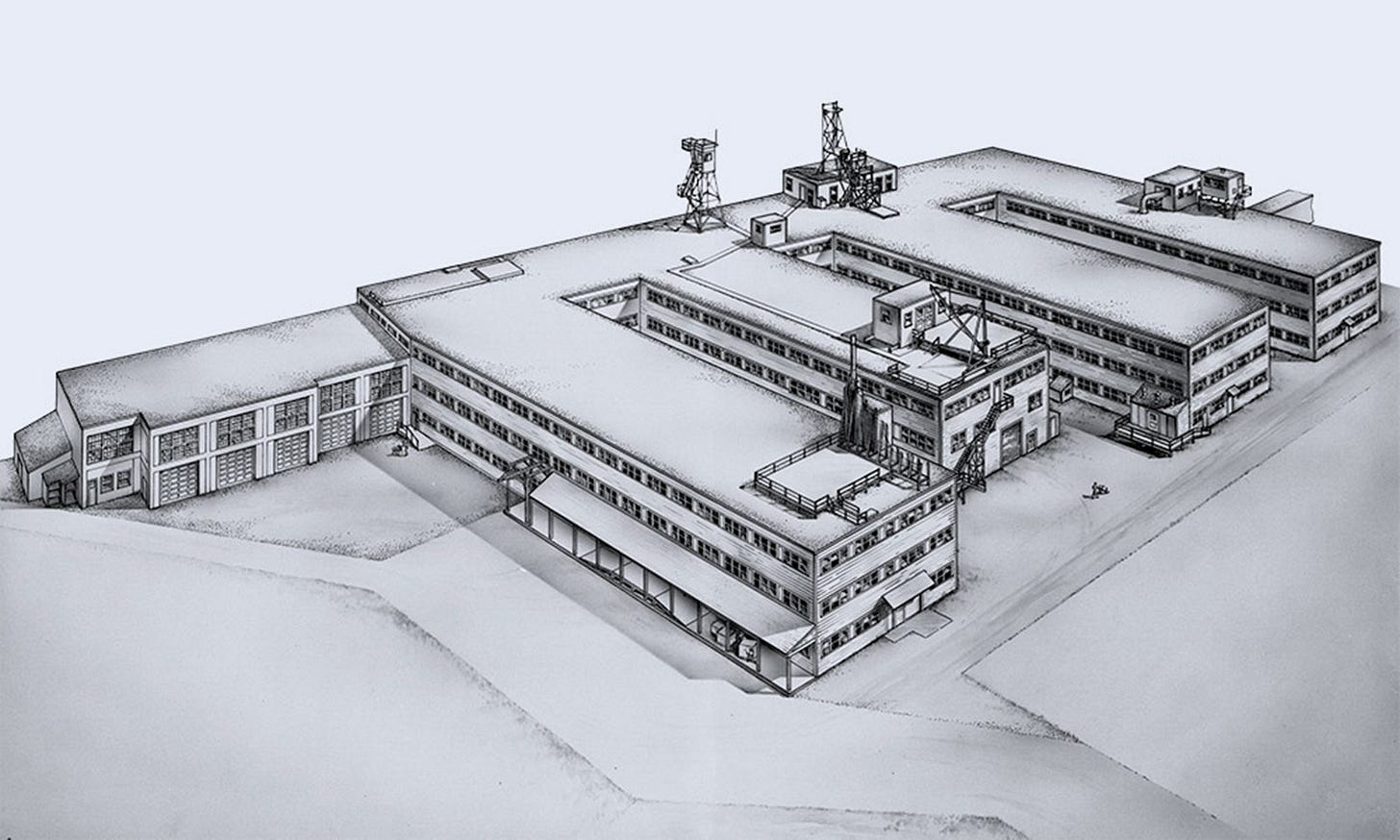

In fact, this was part of the deliberate design of Bell Labs’ architecture.

Members of the technical staff would often have both laboratories and small offices—but these might be in different corridors, therefore making it necessary to walk between the two, and all but assuring a chance encounter or two with a colleague during the commute.

By the same token, the long corridor for the wing that would house many of the physics researchers was intentionally made to be seven hundred feet in length. It was so long that to look down it from one end was to see the other end disappear at a vanishing point.

Traveling its length without encountering a number of acquaintances, problems, diversions, and ideas would be almost impossible. Then again, that was the point. Walking down that impossibly long tiled corridor, a scientist on his way to lunch in the Murray Hill cafeteria was like a magnet rolling past iron filings.

— Jon Gertner, in The Idea Factory

And, indeed, at RAND Corporation as well, where “graduate students rubbed shoulders with full professors in a way unimaginable in most academic departments.”

There were no afternoon teas, formal seminars, or faculty meetings at RAND. Unlike the physicists and engineers, the mathematicians usually worked alone. The idea was that they would work on their own ideas but would help solve the myriad problems encountered by researchers, picking up problems to solve as the spirit moved them. People would drift into each other's offices or, more frequently, simply stop to chat in the corridors near the coffee stations. The grids and courtyards of RAND’s permanent headquarters were designed … by John Williams, as it happens, “to maximize chance meetings”.

— Sylvia Nasar, in A Beautiful Mind

Transcending Disciplinary Boundaries

The result [of using MIT’s Building 20 as an overflow space] was that a mismatch of different departments — from nuclear science to linguistics to electronics — shared the low-slung building alongside more esoteric tenants such as a machine shop and a piano repair facility.

Because the building was cheaply constructed, these groups felt free to rearrange space as needed. Walls and floors could be shifted and equipment bolted to the beams. In recounting the story of Jerrold Zacharias’s work on the first atomic clock, [a New Yorker article] points to the importance of his ability to remove two floors from his Building 20 lab so he could install the three-story cylinder needed for his experimental apparatus.

In MIT lore, it’s generally believed that this haphazard combination of different disciplines, thrown together in a large reconfigurable building, led to chance encounters and a spirit of inventiveness that generated breakthroughs at a fast pace, innovating topics as diverse as Chomsky grammars, Loran navigational radars, and video games, all within the same productive postwar decades.

— Cal Newport, in Deep Work

It is also what made Florence the epicentre of Renaissance art.

This mixing of ideas [in Florence] from different disciplines became the norm as people of diverse talents intermingled. Silk makers worked with goldbeaters to create enchanted fashions. Architects and artists developed the science of perspective. Wood-carvers worked with architects to adorn the city’s 108 churches. Shops became studios. Merchants became financiers. Artisans became artists…

Florence’s festive culture was spiced by the ability to inspire those with creative minds to combine ideas from disparate disciplines. In narrow streets, cloth dyers worked next to goldbeaters next to lens crafters, and during their breaks they went to the piazza to engage in animated discussions.

At the Pollaiuolo workshop, anatomy was being studied so that the young sculptors and painters could better understand the human form. Artists learned the science of perspective and how angles of light produce shadows and the perception of depth. The culture rewarded, above all, those who mastered and mixed different disciplines.

— Walter Isaacson, in Leonardo da Vinci

Or consider DeepMind (now part of Google), which made breakthroughs in protein folding, chess, and Go.

John Jumper, who currently leads the AlphaFold team and was first-author on DeepMind’s 2021 Nature paper, studied physics at Cambridge and worked as Scientific Associate at D. E. Shaw Research before completing his graduate work in theoretical chemistry at the University of Chicago. Demis Hassabis studied computer science at Cambridge, pioneered AI-based videogame design at Lionhead Studios, and completed his graduate studies in cognition and neuroscience at UCL, then MIT, then Harvard.

Once again, we see a spark at the confluence of disciplines and backgrounds. With Jumper and co.’s experience in computation and biology, and Hassabis and co.’s experience building AI for games, the ingredients for AlphaFold are ready. [emphasis added]

—

in his write-up on AlphaFold

Hiring

Since scenius is, by definition, the coming together of bright minds working on a common mission, it is imperative to understand hiring. How are employees selected? How do the early hires represent the culture embodied by the organisation as a whole?

The best way to understand this is by studying the stories of those who did it best.

At PayPal, Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon was required reading — if you enjoyed it, you might be a good fit for the culture. Interview questions to prospective hires included mathematical puzzles.

Imagine you have two ropes of variable density. If you set either rope on fire, despite burning at varying speeds, it will be entirely gone in one hour. Using the two ropes, measure exactly 45 minutes…

There’s a perfectly round table of indeterminate length, and you don’t know the length in advance. Two players have a bag of quarters of infinite depth. Each player can place a coin in the table, and they can touch but not overlap. The last person who puts a coin down on the table and fills it up wins the game. Is there a way to guarantee victory in advance, and does that involve going first or second?

— Jimmy Soni, in The Founders

D. E. Shaw & Co. is famous for asking Fermi estimate questions in their interviews. Given that Jeff Bezos worked there before leaving to start Amazon, it isn’t surprising that they, too, pose such mind teasers.

How many fax machines are in the United States? (D. E. Shaw & Co.)

How many gas stations are in the United States? (Amazon)

— Brad Stone, in The Everything Store

In an early example of “feeder schools”, Bell Labs used to hire Robert Millikan’s best graduate students at the University of Chicago.

Jewett [of Bell Labs] kept writing to Harvey Fletcher, Millikan’s former graduate student who was now in Salt Lake City, sending him every spring for five consecutive years a polite and persuasive invitation to join AT&T. In 1916, Fletcher finally agreed to leave Brigham Young and come work for Jewett.

Millikan, meanwhile, didn’t stop serving as the link between his Chicago graduates and his old friend. In late 1917, responding to an offer from Jewett for $2,100 a year, Mervin Kelly, now done counting oil drops, decided that he would come to New York City, too.

— Jon Gertner, in The Idea Factory

Here’s how the great John D. Rockefeller Sr. went about building the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research.

Rockefeller placed a premium on recruiting the best people for leading positions. “John, we have money,” he told his son, “but it will have value for mankind only as we can find able men with ideas, imagination and courage to put it into productive use.”

That Rockefeller placed scientists, not lay trustees, in charge of expenditures was thought revolutionary. This was the institute’s secret formula: gather great minds, liberate them from petty cares, and let them chase intellectual chimeras without pressure or meddling. If the founders created an atmosphere conducive to creativity, things would, presumably, happen.

— Ron Chernow, in Titan

Autonomy

What do you do after you’ve put candidates through a labyrinth of Fermi estimates, math riddles and 1,000 page sci-fi readings and cherry-picked the best?

The scenius answer: leave them alone.

If Shannon had peculiar work habits before the publication of his information theory, his growing reputation granted him the license to indulge those peculiarities without reservation. After 1948, the Bell Labs bureaucracy could not touch him—which was precisely as Shannon preferred it.

Henry Pollak, director of Bell Labs’ Mathematics Division, spoke for a generation of Bell leaders when he declared that Shannon “had earned the right to be non-productive.”

Shannon arrived at the Murray Hill office late, if at all, and often spent the day absorbed in games of chess and hex in the common areas. When not besting his colleagues in board games, he could be found piloting a unicycle through Bell Labs’ narrow passageways, occasionally while juggling; sometimes he would pogo-stick his way around the Bell Labs campus, much to the consternation, we imagine, of the people who signed his paychecks.

— Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman, in A Mind At Play

A strikingly similar environment was at RAND Corporation.

All but one or two of the mathematicians, including Nash, came to work in short-sleeved shirts. Appearances were so casual that one mathematician, who found it all very déclassé, felt obliged to rebel by wearing a three-piece suit and a tie to the office every day…

The mathematicians were, as usual, the freest spirits. They had no set hours. If they wanted to come into their offices at 3:00 A.M., fine. Shapley, who had come back from Princeton for the summer and continued to insist on the sanctity of his sleep cycle, was rarely seen before midafternoon. Another man, an electrical engineer named Hastings, typically slept in the “shop” next to his beloved computer.

Lunches were long, much to the annoyance of RAND’s engineers, who prided themselves on sticking to a more respectable routine. The mathematicians mostly took their bag lunches to a conference room and pulled out chessboards. They invariably played Kriegspiel, usually in total silence, occasionally punctuated by a wrathful outburst from Shapley, who frequently lost his temper over an umpire’s or opponent’s error.

Here’s what an early PayPal employee said about the culture.

[PayPal] hired really good people, gave them a lot of trust, and so people ran at their own pace, just made sure that they checkpointed to make sure we were in sync occasionally. And then we would just keep on running. So they got the best out of some very, very smart people.

— Santosh Janardhan, in The Founders

For those interested in books about scenius, I recommend Sylvia Nasar’s A Beautiful Mind (RAND Corporation and Institute for Advanced Study), Sebastian Mallaby’s The Power Law (Silicon Valley), Jimmy Soni’s The Founders (PayPal), and Jon Gertner’s The Idea Factory (Bell Labs).

There are also some wonderful articles about scenius. My favourites are these ones by Kevin Kelly, Packy McCormick and Infinite Loops.

This essay has wonderful insights from Abraham Flexner, the founding director of IAS.

Feedback and reading recommendations are invited at malhar.manek@gmail.com

![John Nash on AI in 1954 [source: George Dyson (@gdyson@sciencemastodon.com)] : r/IsaacArthur John Nash on AI in 1954 [source: George Dyson (@gdyson@sciencemastodon.com)] : r/IsaacArthur](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CHNT!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4c8f39a6-ff01-44c7-90c4-5b2839090b1f_640x833.jpeg)