I love reading. To me, books are the distillation of a lifetime’s worth of wisdom. Some books entertain you, others make you smarter — and then, there are books that create magic. Books that stir you up, ignite a flame of thoughts, leave you with a burning fire of ideas.

Gödel, Escher, Bach was the first time I experienced magic. Zero To One was the second.

I have since become a huge fan of Peter Thiel, voraciously listening to his podcasts, pouring over Blake Masters’ original class notes, and scouring the internet for anything he has written (like this treasure trove). Not to mention reading Cryptonomicon (which was required reading at PayPal), The Founders (a book about PayPal — I even spoke with the author), and René Girard’s writings (as we’ll see soon).

Here is my understanding of Peter Thiel’s philosophy — or, as I like to call it, Thieleology. An overview of this essay:

Anti-Anti-Anti-Anti Contrarian

An Education in Philosophy

Competition is for Losers

Hunting for Secrets

The Applied Philosopher

Definite Optimism

The Motivation Question

With Peter Thiel’s Complements

Some Contrarian Truths

Bonus!

If there is one thing I hope to convey through this essay, it is a better appreciation for the rich connections between Thiel’s various ideas.

Disclaimer: I have never met Peter Thiel (though, as an admirer, I would love to). All wisdom is Peter’s; any mistakes are mine.

First, who is Peter Thiel, and why should you care? Peter co-founded Confinity in the 1990s, which later merged with Elon Musk’s X.com to form the PayPal we know today. He was the first outside investor in Facebook, and his VC firm Founders Fund has made legendary investments in SpaceX, Stripe, Palantir and others. Among other things, he has been a big backer of JD Vance’s political career and has set up the Thiel Fellowship, which gives college dropouts $100K to build something.

This is Peter Thiel as the world knows him. But who is he, really? That’s what this essay is about.

Anti-Anti-Anti-Anti Contrarian

(Inside joke: this weird subheading is inspired by Thiel’s talk titled “anti-anti-anti-anti classical liberalism”)

Today, Peter Thiel is famous for his contrarian question: ‘What important truth do very few people agree with you on?’ He is well-known for backing unconventional founders, from Mark Zuckerberg to Elon Musk. But once upon a time, Thiel was as close to the dictionary definition of ‘conventional’ as one could possibly be.

In his 8th grade yearbook, a friend predicted that Thiel would go to Stanford for college. Not only did this prediction come true, Thiel continued on at Stanford Law School, and almost became a Supreme Court clerk. The man famous for being contrarian was once knee-deep in the rat race of prestige.

What changed this? I reckon there were 2 big influences.

First, Thiel studied under René Girard at Stanford — a name that will keep recurring throughout this essay.

René Girard says there are two kinds of desire: physical and metaphysical desire. Physical desire is wanting an object for its inherent qualities, like a glass of water because you’re thirsty — or learning for the sake of learning. This is healthy.

Metaphysical desire is different. Acquiring the object only brings you joy because of the person it makes you become. You only care about it because of what it says about you — like learning for good grades or a diploma. This is unhealthy.

The second — the late-90s business battle of PayPal v/s X.com — is more nuanced, and leads us to our next topic of discussion.

An Education in Philosophy

Ever since I learnt that Thiel studied philosophy in college, I’ve wanted to get a sense for what an academic study of philosophy actually looks like. So, my first quarter at the University of Chicago, I took a class called Philosophical Perspectives.

From what I’ve understood, academic philosophy forces you to think deeply about complicated questions. For example, when we read Oedipus Tyrannus for our class, we were asked to think about questions like, is it the story of a rise or a fall? Is Oedipus better off at the start or the end of the play? If a king is someone who is born into monarchy and a tyrant is someone who earns the crown through their efforts, was Oedipus the king or the tyrant of Thebes?

More generally, philosophy asks questions like, to what extent does meaning reside in the interpreter v/s the message? Is there free will? Do we compete because of our similarities or our differences? Is interiority a complement or a substitute to exteriority?

There are no straightforward answers to such questions. My professor kept telling us that the key to success in academic philosophy is the ability to take a risky, unconventional stance, and then back it up with reasoning and textual evidence.

A great philosophy paper, my professor explained, involves sticking your neck out by arguing for a bold, contrarian thesis — for example, saying that Oedipus is better off at the end, when he is blind, exiled and disgraced, than at the start, when he is the beloved ruler of Thebes — and then corroborating the thesis by logical reasoning and evidence.

Seen through this lens, one can see hints of a philosophical mind in all of Thiel’s talks and writings: contrarian beliefs grounded in facts.

Competition Is For Losers

One of the questions that philosophy is concerned with is, do we compete because of our similarities or our differences? René Girard thinks, as does Thiel, that we compete with those who are similar to us.

Paradoxically, I think the polarization masks the increasing sameness of the two major parties. They hate each other more and more, as they become more and more alike, like the Capulets and the Montagues in “Romeo and Juliet”...

— Peter Thiel, Reddit AMA

As René Girard’s mimetic theory of desire suggests, metaphysical desire arises when we compete for the same things.

Overachieving high school students with the same application profiles — strong GPA and near-perfect SAT scores, student council, model UN, ‘research’, internships — fight tooth and nail over admissions into the same few elite universities. In this case, the physical desire of learning and seeking knowledge for its own sake gives way to the metaphysical desire of the ‘Ivy League’ brand value.

Browsing the merch store of an elite university is an insightful experience: you realise how people are willing to pay $100 for a Harvard hoodie; take away that logo and they probably wouldn’t pay $20 for it. Elite-college-bookstores are the unseen version of Louis Vuitton.

Once they reach college, most of these high-flying high-schoolers get funneled into the same few paths — pre-med, computer science, economics/finance — and compete fiercely over the most prestigious on-campus clubs and internships. Many go on to chase the same few jobs — consulting, finance, AI — even the STEM majors get enticed into quant hedge funds — and the new brand on the resume becomes Goldman Sachs.

Guess what? The passion project that you have so much fun doing (this blog, in my case) doesn’t bolster your resume; a prestigious brand name does. By competing with others, you are competing away the stuff that makes you interesting. Competition is for losers. (There is a caveat to this: competing with others is awful; competing with yourself, though, can be magical. More on this soon).

If you’re in the US and go to a good school, there are a lot of forces that will push you towards following train tracks laid by others rather than charting a course yourself. Make sure that the things you’re pursuing are weird things that you want to pursue, not whatever the standard path is. Heuristic: do your friends at school think your path is a bit strange? If not, maybe it’s too normal.

Ardent Thiel-interview-watchers know that he often brings up the question of what education is in economic terms. What does the value of education derive from? Is it an investment? A consumption good (“four year party”)? An insurance policy?

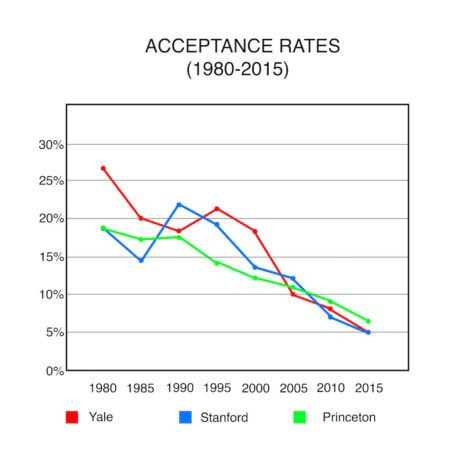

Thiel’s answer — which makes perfect sense when you understand his ideas on competition and Girardian mimetic desire — is that education is a tournament. The value of education in today’s world, Thiel thinks, derives primarily from the fact that the elite universities exclude people. Just like the long queues of people waiting to just enter a Louis Vuitton store, the more exclusive you make it, the more valuable it gets.

To untie the knot of desire, we have only to concede that everything begins in rivalry for the object. The object acquires the status of a disputed object and thus the envy that it arouses in all quarters, becomes more and more heated…

The value of an object grows in proportion to the resistance met with in acquiring it. (Read: the value of the Ivy League is inversely proportional to its acceptance rates). And the value of the model grows as the object’s value grows. Even if the model has no particular prestige at the outset, even if all that ‘prestige’ implies — praestigia, spells and phantasmagoria — is quite unknown to the subject, the very rivalry will be quite enough to bring prestige into being.

— René Girard, in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World

Ordinarily, businesses increase supply in response to a surge in demand — except, like LVMH, the elite colleges don’t do this. If the role of the university is primarily to impart knowledge, it would make sense for them, Thiel thinks, to expand class sizes, so that they can educate more people. On the other hand, if the primary role of the university is to act as an exclusive club, then their current behaviour makes complete sense. The plummeting acceptance rates and skyrocketing tuition fees for top colleges over the last few decades seems to corroborate Thiel’s thesis.

Back to the story of a young Thiel climbing the rat race of prestige. Thiel explains in this interview that his mistake was to assume that education is a substitute for thinking about one’s future.

What are you going to do in life? I don’t know, I’ll get an undergraduate degree. What will you do after that? I don’t know, I’ll get a postgraduate degree. What will you do after that? I don’t know, I’ll work at a hedge fund/law firm/consulting firm and so on…

“The 24-year-old Peter Thiel had no plan whatsoever. A bad plan would have been better.”

— Peter Thiel

Hunting For Secrets

René Girard’s most famous book was literally titled Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World: a profound clue for the Thieleology aficionado.

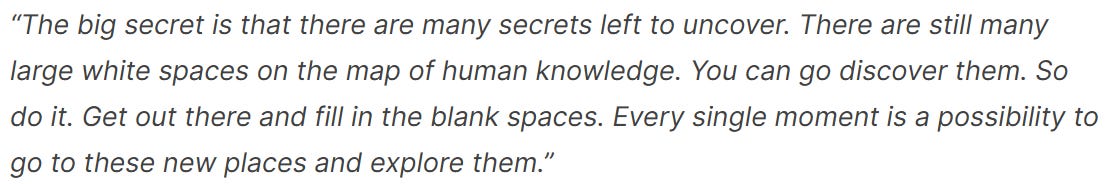

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Thiel emphasises the importance of secrets — Things Hidden — as truths that lie somewhere between popular knowledge and unanswerable mysteries. Think of secrets as a 3-layer cake.

The first layer is fundamental v/s emergent. Physics and mathematics are fundamental. Economics, politics and psychology are emergent.

The second layer is contrarian v/s consensus. Contrarian ideas are those that very few people believe. Consensus ideas are mainstream, popular views.

The third layer is truth v/s falsehood.

Secrets, then, are simply contrarian truths. Fundamental contrarian truths are secrets of nature. Emergent contrarian truths are secrets of people. In the Bhagavad Gita, choosing Krishna over his entire army was Arjuna’s contrarian truth.

Secret = Contrarian Truth

Unravelling secrets of nature is what mathematicians, physicists and astronomers do. Einstein’s theory of relativity was a secret of nature, since it was a contrarian idea (against the well-established, mainstream Newtonian theory) and it revealed a new truth about the universe.

Secrets of people are, in some sense, like the memo from Jerry Maguire: things we think but do not say. If discovering secrets of nature won Einstein the Nobel Prize, finding secrets of people skyrocketed Seinfeld to worldwide fame.

“[Claude Shannon is] a decidedly unconventional type of youngster” — Vannevar Bush (Shannon’s PhD advisor)

[Claude Shannon] had this counter-culture streak about him, and he was a non-conformist in the best sense. (From Jimmy Soni’s Reddit AMA)

Rory Sutherland’s book Alchemy — everything he writes and says, for that matter — is a masterclass on the craft of discovering people secrets. A few of my favourites from him: cyclists tend to be rude since they pay the price for losing momentum; the hidden role of dishwashers is to hide dirty dishes; specificity can act as a placebo. (My interview with him below).

EVs, Costly Signalling and Alchemy with Rory Sutherland

I recently had the opportunity to speak with one of my favourite thinkers and writers, Rory Sutherland. He is the vice-chairman of Ogilvy and an absolute creative genius, as you will find out for yourself if you read his brilliant book Alchemy (which I can’t recommend highly enough) or watch his Ted Talks.

Peter Thiel even helps us out by providing a general framework to think about contrarian truths: “most people think X, but the truth is the opposite of X”.

At this point, we can make sense of Thiel’s disdain for buzzwords, for they are the most obvious instance of the mainstream and the consensus.

“Big data” really means “dumb data.” — Peter Thiel, Reddit AMA

The Applied Philosopher

Most people think Zero To One is a business book, but the truth is that it is a deeply philosophical tome on how to build the future. Most people think Peter Thiel is a startup investor/tech VC, but the truth is that he is a profound thinker who applies his philosophy to startups and investing.

In Thiel’s view, the future is not simply a time that hasn’t yet occurred. It is a time that will be different from the present. If the world does not change significantly in the next 50 years, the future is still far away.

Moreover, Thiel thinks, the future will not be built by a single individual working alone, nor by large, bureaucratic, corporate organisations — the perfect middle ground, he thinks, is a startup.

Positively defined, a startup is the largest group of people you can convince of a plan to build a different future. A new company’s most important strength is new thinking: even more important than nimbleness, small size affords space to think.

— Peter Thiel, in Zero To One

Here is an example of Thiel’s philosophy of secrets, applied to startups.

Biggest mistake ever was not to do the Series B round at Facebook.

General lesson: Whenever a tech startup has a strong up round led by a top tier investor (Accel counts), it is generally still undervalued. The steeper the up round, the greater the undervaluation.

— Peter Thiel, Reddit AMA

Another example, on the business version of ‘competition is for losers’:

Most people believe that capitalism and competition are synonyms, and I think they are opposites. A capitalist accumulates capital, and in a world of perfect competition all the capital gets competed away: The restaurant industry in SF is very competitive and very non-capitalistic (e.g., very hard way to make money), whereas Google is very capitalistic and has had no serious competition since 2002.

— Peter Thiel, Reddit AMA

The best companies, as per Thiel, are born out of a secret (i.e., a contrarian truth), and use the cash flows that accrue from their secret to invest in deepening their monopoly.

Another secret in the business context is that the overwhelming majority of a tech startup’s present value accrues from future cash flows in years 10 and beyond.

Most of a tech company’s value will come at least 10 to 15 years in the future…

In March 2001, PayPal had yet to make a profit but our revenues were growing 100% year-over-year. When I projected our future cash flows, I found that 75% of the company’s present value would come from profits generated in 2011 and beyond—hard to believe for a company that had been in business for only 27 months. But even that turned out to be an underestimation…

If you focus on near-term growth above all else, you miss the most important question you should be asking: will this business still be around a decade from now? Numbers alone won’t tell you the answer; instead you must think critically about the qualitative characteristics of your business.

— Peter Thiel, in Zero To One

Definite Optimism

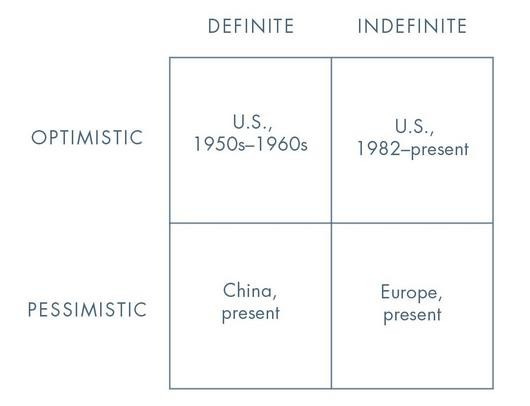

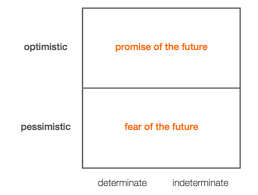

Now that we know what matters — secrets — the question is, how do we find them? To this, Thiel proposes a 2x2 matrix.

Remember, the future is a time that will be different from the present. Whether you think it will be better or worse than the present relates to optimism and pessimism.

Definite and indefinite pertains to whether your view of the future is grounded in a concrete plan or left to randomness. Thiel likens this to the difference between calculus (definite) and statistics (indefinite): calculus can concretely predict the behaviour of a system, while statistics can only ever make a vague, probabilistic estimate of the possibilities.

Definite optimism works when you build the future you envision.

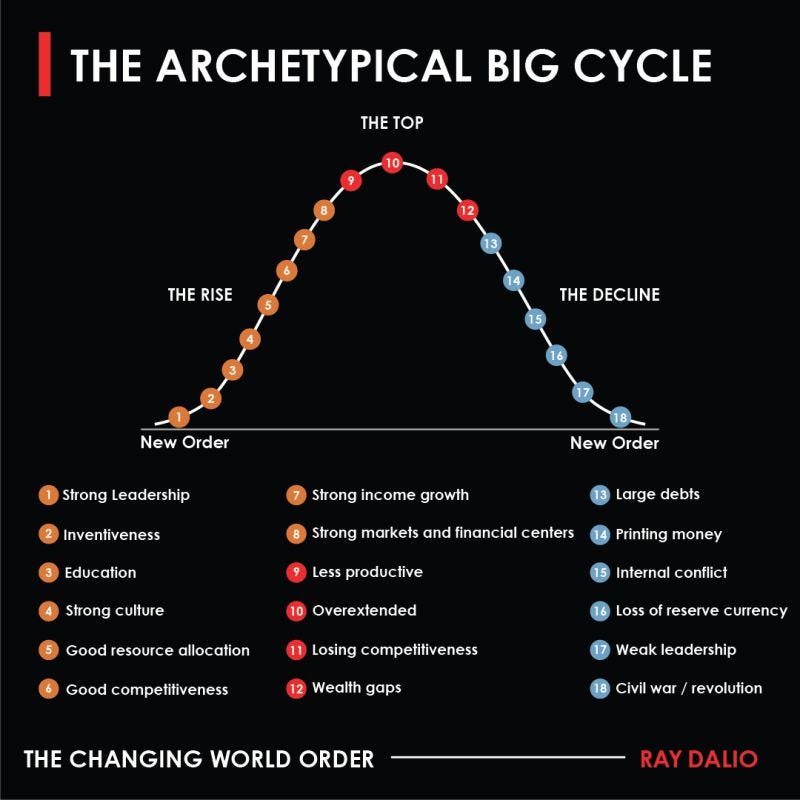

There are many ways one can think about this matrix. The version with a country/society in different stages is above. In fact, this relates to Ray Dalio’s model of changing world orders: a country is in the strongest phase of the world orders cycle when it is definite and optimistic (education and leadership being the leading indicators), and in the weakest phase when it is indefinite and pessimistic (loss of reserve currency status).

One could hypothesise that world order cycles proceed from definite pessimism —> definite optimism —> indefinite optimism —> indefinite pessimism.

Another version, with different occupations, is below.

Yet another version, with investment and savings, is below.

I love Iyengar yoga because it deeply ingrains in me the concept of definite optimism. Supreme health and control over the body and breath are possible (optimism), with effort and perseverance (definite).

Reddit user: Hi Peter … if you were not from United States, do you believe you could reach the same position as you are now?

Peter Thiel: One can never run this experiment twice, but...

I was born in Germany and my parents emigrated to the US when I was 1 year old. I think Germany and California are in some ways extreme opposites — Germany is pessimistic and complacent, California is optimistic and desperate. I suspect my life would have turned out very differently had we stayed in Germany.

***

Reddit user: What do you think is the most exciting example of a company showing “determinate optimism” today?

Peter Thiel: The dual Elon Musk empire of Tesla and SpaceX. (For context, this is from 2014)

A definite world rewards conviction; the below excerpt from More Money Than God is fascinating.

One time the macro men feared that the markets would turn against their European bond position in the short term, and they advised [Julian] Robertson to protect Tiger from losses by putting on a temporary hedge.

“Hedge?” Robertson retorted angrily. “Hey-edge? Why, that just means that if I’m right I’m going to make less money.”

“Well, that’s right,” the macro men answered him.

“Why would I want to do that? Why? Why? That’s just dirt under my fingernails.”

— Sebastian Mallaby, in More Money Than God

The Motivation Question

At one point during their podcast, Joe Rogan asks Peter Thiel about the Egyptian pyramids. The clip is almost funny to watch: Rogan keeps asking ‘how’ they built the pyramids, while Thiel keeps evading the question and focuses on ‘why’ they were motivated to build them. As David Perell writes, “[Thiel] doesn’t just focus on the brushstrokes. He looks at how the painting is framed.”

If you believe that ‘where there is a will there is a way’ (as a definite optimist would), then it is obvious that the important question to focus on — the constraint, the bottleneck — is not ‘what is the way?’ but ‘what is your will/motivation?’

Similarly, consider Thiel’s insights on AI from 2014:

I think AI is still a fair ways off. But the economic questions (e.g., how will this impact our work?) are secondary to the political questions (e.g., will AI be friendly?).

The development of AI would be as momentous as the landing of extraterrestrials on this planet. If aliens landed, the first question would not be about the economy!

With Peter Thiel’s Complements

Perhaps you noticed the typo — but that was intentional! For one of the overarching contrarian truths in Peter Thiel’s philosophy is

Most people think in terms of substitutes (x or y), but it is often more valuable to think in terms of complements (x and y).

Reddit user: When you backed Elon Musk with SpaceX, was it because you believed in/knew Elon, thought space travel was important, or because you were looking for a return?

Peter Thiel: All three.

In his podcast with Joe Rogan, Thiel asks the question of interiority (focus on inner self as in Eastern philosophy, e.g., yoga, meditation) v/s exteriority (focus on outer world as in Western philosophy, e.g., material possessions, space travel) — are they complements or substitutes? Is improving the inner self a first step that enables external progress? Or is it a substitute where attention is reallocated from external exploration to inner consciousness?

My personal answer is that they are complements, which also fits well with the ancient Greek idea of man as a mini-world:

What made Vitruvius’s work appealing to Leonardo and Francesco was that it gave concrete expression to an analogy that went back to Plato and the ancients, one that had become a defining metaphor of Renaissance humanism: the relationship between the microcosm of man and the macrocosm of the earth.

This analogy was a foundation for the treatise that Francesco was composing. “All the arts and all the world’s rules are derived from a well-composed and proportioned human body,” he wrote in the foreword to his fifth chapter. “Man, called a little world, contains in himself all the general perfections of the whole world.” Leonardo likewise embraced the analogy in both his art and his science. He famously wrote around this time, “The ancients called man a lesser world, and certainly the use of this name is well bestowed, because his body is an analog for the world.”

— Walter Isaacson, in Leonardo da Vinci

On the question of interiority, I also resonate strongly with a quote from the Stoic philosopher Epictetus: “What else is tragedy but the portrayal in tragic verse of the sufferings of men who have devoted their admiration to external things?”

This brings us to a topic we touched on earlier. Competing with oneself — say, by periodically reflecting, introspecting and course-correcting — as opposed to competing with others, is an element of interiority. In fact, the Hindi language has distinct words for these, derived from Sanskrit: प्रतिस्पर्धा implies competing with others, while अनुस्पर्धा implies competing with yourself (those familiar with Hindi should watch this video). Google Translate, interestingly, obscures the difference:

As you think about this, I would encourage you to connect the dots with other aspects of Thieleology. Here is my synthesis:

The motivation (why) question relates to optimism v/s pessimism, which relates to interiority (what drives you to do something? Curiosity, ambition, revenge? Do these motivations pertain to a brighter future or a gloomier one? How does understanding your motivations improve your understanding of yourself?)

The engineering (how) question relates to definite v/s indefinite, which relates to exteriority (do you have a concrete/definite plan to implement your vision or a vague/indefinite perspective? How do you need to engage with the external world to execute your plans?)

Therefore, interiority and exteriority are complements, which, when optimally aligned, lead to definite optimism (building the future you envision).

Some Contrarian Truths

Inspired by Zero To One, I have a section in my personal notes Google Doc where I note down contrarian truths that I think of. My list has 23 contrarian truths as of now; here are my favourites.

Most people think that building good habits requires ‘willpower’ and ‘self-control’ in avoiding temptations, but the reality is that building systems and minimising friction matters more.

Most people focus on the demand side, but supply is more important (Marathon Asset Management, Capital Returns).

Most people focus on probabilities, but payoffs are more important (Nassim Taleb, The Black Swan).

Most people think The Shawshank Redemption is a prison escape movie, but in fact it has deep philosophical meaning, e.g., power of writing, perseverance (tunnelling through the wall), power of knowledge/education etc.

Most people focus too much on what to do (e.g., what book to read), but when to do something matters more (e.g., when to read it) — what is the right time — As Morpheus says in The Matrix, “more important than what is when”.

Most people think entrepreneurs take risk, but the reality is that they minimise it.

Every deep thinker must necessarily think deeply about the meta question, ‘what questions are worth thinking deeply about?’ Every deep thinker must not only play a game well, but also, importantly, ask what games are worth playing.

Most people think in terms of substitutes (A or B), but the truth is that complements are more valuable (A and B): man and machine, fundamentals and technicals in investing, top down and bottom up, interiority and exteriority.

Most people often (implicitly) choose to succeed at trivial things, but it is better to fail at nontrivial things. Poverty of ambition is underrated.

Thiel says there are two views of philanthropy: the American view is that the philanthropist is a selfless person with a desire to give back to society; the European view is that the philanthropist is atoning for their wrongdoings by giving up wealth. Thiel agrees more with the European view.

Similarly, if you are getting 100% on an exam, the consensus interpretation is that you are doing very well. The contrarian view, that is worth considering, is that maybe you are not taking a sufficiently challenging class.

Likewise, if you are not falling while learning ice skating or skiing, that means you are not trying enough.

Elon Musk is a big advocate of deleting things from a manufacturing process — he says that if you don’t end up adding things back later, it means you aren’t deleting enough.

Bonus

Reddit user: Do you follow sports? What's your favourite sport? Favourite team?

Peter Thiel: In the Soviet Union, chess was considered a sport — and I think that’s the one thing the communists got right.

So, you’re intrigued after reading this essay and want to learn more about Thiel?

Here’s my favourite Thiel video, one that I would very strongly recommend watching:

I thoroughly enjoyed reading David Perell’s essay about Peter Thiel, and would highly recommend it. Some excerpts below:

Some of Thiel’s favourite books:

Feedback and reading recommendations are invited at malhar.manek@gmail.com

What a masterpiece this is! Please do send this to Peter Thiel and I am sure he'd love to meet you :)